I been thinking a lot about this one old friend of mine lately. He isn’t someone I saw with much frequency when I lived in New York. In fact in the past few years we really only saw one another twice a year, at Passover and Hanukkah. Other than that we’d run into each other at a show or a party, incidental meetings. Occasionally we would make a plan to drink coffee on a bench in Tompkins Square Park, something we had done often in our early-20s. But those rendezvous occurred less often as we got older and our lives began to take shape in more substantial ways than they had when we were young.

That said, there is an intimacy in our friendship and the way we communicate that feels profound. There’s been an expectation of longevity that other similar relationships don’t have. During our afternoons on the park bench, we would often joke about our future as old men. It started because of an experience I’d had on bus. There had been an elderly gentleman sitting in a single seat, with an empty seat behind him, clutching a paper bag tightly in both hands. I sat on the bench opposite his and watched him intently. He seemed to have such a sense of purpose, clutching his bag like that.

A stop or two later, another elderly man got on the bus and sat in the empty seat behind the first man, whom he had nodded at familiarly as he’d boarded. While he lowered himself into his spot, he placed a hand on the first man’s shoulder and squeezed—a small gesture, but one that seemed significant. The first man opened his paper bag and removed two identical sandwiches. Tuna salad, by the smell of it, on untoasted white bread. He handed one to his companion, folded the paper bag and put it in his pocket, and then they silently began to eat. They finished their sandwiches right as the bus reached the park, where they slowly disembarked together. It was a brisk autumn day and I remember wondering if they would be cold. The ritualistic nature of their interaction fascinated me and for a time I thought about them incessantly. How close were they? How long had they known each other? Did they ever speak? Were they just friends because they lived on the same bus line and were roughly the same age?

Later that week I was in the city at the coffee shop all the punks used to hang out at on Avenue A and I ran into my friend. We took our coffee into the park and sat smoking on a bench. I told him about the two men and we joked that one day we would be the two old Jewish guys on the bus, moving slow, eating stinky food. “I can’t wait.” I told him.

“I can’t wait till we have to make the kid at the bodega heat our coffee extra in the microwave because we’ve been smoking so long we can’t feel anything in our mouths anymore.” he countered.

“I can’t wait until we don’t understand young people,” I replied as a group of teens walked by.

I’ve never been a Live Fast Die Young guy, but most of my friendships don’t include an expectation that we’ll be old together. My relationship with this particular friend is unique in that regard. And that’s part of why it was so jarring when he called me to tell me he was sick. “I’ve got ALS. I’m picking out my wheelchair today,” he said. We talked for a minute, about what had happened. He’d been diagnosed right before Thanksgiving but wanted to wait until after the holidays to let people know.

When I flew home in December for Christmas I went straight from JFK to see him. Sitting on the Airtrain, I started thinking about the decade or so that we’d known each other. I thought about the first time I’d gone to his parents’ apartment, before he’d even moved out. I thought about the first time he’d come over to my place on Lorimer Street when we were just beginning to become friends. I thought about all the times we’d hung out, but I also thought about the spaces in between, all the times I hadn’t seen him. One thing I’ve long admired about him is the fact that he never really pulled any punches. He was blunt and direct, in a way that wasn’t insensitive, but wasn’t necessarily sensitive either. And one of his complaints throughout the years was that he felt taken for granted, or worse, excluded. I never felt like he was leveling that accusation at me, but I always felt like he could have if he wanted to. That he was sparing me from hearing it because he knew I knew already.

And so sitting on the train I started to wonder what he thought about all these people suddenly coming over to see him. I thought about the fact that I probably wouldn’t have been going straight to his house from the airport if he wasn’t sick, and it occurred to me that this same thought had most likely crossed my friend’s mind as well.

When I got to the apartment I sat down at the dining room table and his mother wheeled him out from his room. We drank seltzer like good Jewish boys and shot the shit. We hadn’t seen each other since Passover, probably, so there was a lot of catching up to do. His band had just recorded a full length for a pretty big local label. It was during the recording process that he realized that something was wrong, because he was getting so tired and feeling so weak all the time. Doctor’s eventually figured out it was ALS, a neurodegenerative disease that slowly kills off the nerve cells in the body. Pretty soon he was using a walker and he just moved onto the wheelchair and that’s where it’s at now. “I’ve got two to five from the onset of the disease and I probably had it for a year before I was diagnosed,” he told me matter-of-factly. He’s got the same frankness about his own mortality as he does about everything else.

Conversation moved on to all the different friends that had been through and visited, and then we got to the point in the conversation I’d been afraid of on the Airtrain. “You know, these people keep coming over, people that I haven’t seen in forever, and it’s so great that everyone gives a shit about me. And I started thinking about how mad I used to be all the time at all these people that I thought weren’t calling me enough,” he paused to catch his breath and I waited for the indictment, the moment when he would force me to acknowledge that I was one of those people. “And then I realized I wasn’t really calling them either. I just think it isn’t worth it to be so mad all the time. At the end of the day I got a lot done and I had a ton of really great friends and all the stuff I felt so mad about seems pretty inconsequential.”

Other people filtered in, soon there was a whole crew hanging out. I ordered some pizzas, people told stories, it was a nice time. I left feeling sad but heartened, my friend seemed to be in high spirits, like he enjoyed all the company. It’s weird to say, but he wears his illness well, or at least as well as one can.

A few days later at my parents’ house I broke down crying. I’d been running around the city trying to catch up with everyone I don’t get to see in Texas and it wasn’t until I was stationary that everything hit me all at once. I felt so sad and so angry all at the same time. And listen: I know this isn’t about me. I’m not the one that’s sick, I’m not doing the day-to-day caretaking. I know I’m not the one most affected here and my perspective isn’t the most important. I just want to make sure that’s clear. But this is someone I care about and I’m trying to work out my emotions and I think this is an okay space for that.

I saw my friend again before I left town, at the tattoo shop our pal Sue works at. He wants to get covered before he dies, and Sue called a shop meeting where everyone that works there agreed to tattoo him for free. It’s so good to see people getting together to mitigate the fucking awfulness of all this, but it’s still so stupid that he’s sick in the first place. Like, it just seems incredibly unfair.

You know that Jack Palance Band song “How Can I” on the JPB / ADD/C / Queerwülf three-way split? I think I’ll leave you with a few lines from that. My records are still in storage in New York so the lyrics may not be right but here goes:

How can I live, when I know things are coming I just can’t take? / How can I live, when I know that my heart’s gonna have to break again? / It’s just like my buddy Mike Pack says / he says, “always tell your friends you love ‘em, because you never know when goodbye’s gonna be goodbye.”

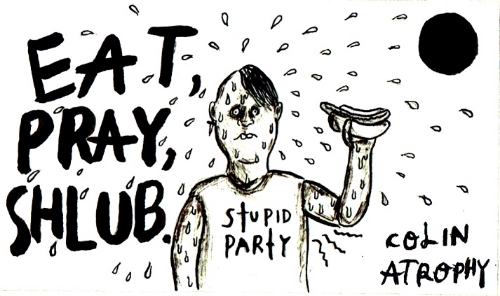

Postscript: This column was about my friend Dan Klein who passed away this morning. I'm not sure what else to say right now, but I'm very grateful for the music that he recorded, the photos and memories I have. I'm so lucky to have been friends with this mensch.